Research

I am interested in understanding the neural basis of sensory experience.

Primary sensory neurons, such as cone photoreceptors, gather real-time information about the environment for the purpose of influencing the organism’s behavior. The samples are relayed to downstream centers in the form of discrete action potentials. Those signals, however, are often noisy and ambiguous, as many perceptual illusions demonstrate.

To minimize ambiguity, the brain leverages at least three sources of information during perceptual processing: 1) feed-forward signals from sensory neurons, 2) prior experience and 3) feedback signals. The purpose of my work is to understand how incoming sensory input is incorporated with other sources of sensory information to produce a coherent interpretation.

Current projects

My postdoctoral research investigates the neural mechanisms underlying elementary visual processing with a technique called adaptive optics. Adaptive optics is a tool for measuring structure and function of the retina at a cellular scale in human subjects. I use adaptive optics to simultaneously image and stimulate identified cone photoreceptors in human subjects and record their perceptual experience. A stimulus that falls on only a single cone is under-sampled from the perspective of color vision – the brain is missing information from the other two classes of cones. For this reason, the brain is forced to rely on prior experience when judging the color of each tiny spot.

The motivation of this work is to understand how the visual system creates a meaningful sensory experience of the external world from the signals that are encoded by the cone mosaic. In our initial experiments, we mapped, for the first time, the spatial topography of color percepts at the level of the cone mosaic. Across trials, a single cone tended to yield a consistent color sensation. The greatest predictor of the color reported was the cone-type probed. This observation suggested that the visual system possesses prior information with sufficient resolution to remember the spectral identity of each cone. Together, this work has implications for our understanding of the basic mechanisms sub-serving color and spatial vision and could potentially be leveraged when optimizing retinal prosthetics.

Imaging cells in a living human eye

The first step towards probing vision on a cellular scale is to image photoreceptors with a camera.

Eye doctors routinely use an imaging tool called an ophthalmoscope to peer at the back surface of a patient’s eye. Such examinations provide a lot of useful information for detecting and diagnosing disease. Unfortunately, the resolution of a standard ophthalmoscope is quite poor. Only the largest structures, such as major blood vessels and the optic nerve head, are visible - single cells are much to small to be resolved. This is because the surface of the cornea and lens are riddled with small imperfections.

Adaptive optics is a technology that allows us to fix those imperfections and see the very smallest structures - cone and rod photoreceptors.

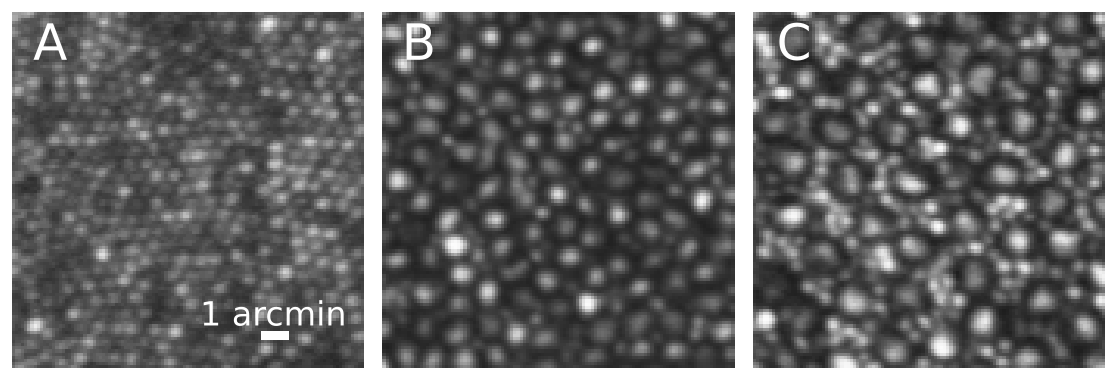

Above are a series of adaptive optics image taken of my right eye at three different retinal locations. The left image (A) was taken at the very center of my retina, the foveola. Cones here are very small (each blob is a single cone). This is the area used for reading fine print. The middle image (B) was 1.5 degrees away from the center of gaze. At this location cones become larger in size and rods (the smaller blobs) are found in about equal number to cones. The image to the right (C) was 5 degrees away from the foveola. Here rods become clearly visible and more numerous than cones. Scale bar = 1 arcmin or about 5 microns. For reference, the width of a human hair ranges from 30-100 microns.

Single cone psychophysics

Read more about probing visual sensation at a cellular scale.

Below is a video taken during an experimental session.

The first computer monitor shows a live image of a cone mosaic. The left panel is an unstablized video. The right panel, with a black box surrounding the mosaic, is a stabilized view. The subject’s natural eye-movements are corrected in real-time. This monitor also contains a pupil tracker (bottom right) and the software that controls stimulus delivery (red rectangle on the right side). As the video pans to the left, a second monitor shows the real-time wavefront measurements and the adaptive optics control loop. Auditory feedback beeps can be heard. These sounds indicate the start of each trial and each button press. Auditory beeps also indicate when the pupil has moved more than a specified tolerance.