Imaging cells in a living human

Adaptive optics ·The first step towards probing vision on a cellular scale is to image photoreceptors with a camera.

Eye doctors routinely use an imaging tool called an ophthalmoscope to peer at the back surface of a patient’s eye. Such examinations provide a lot of useful information for detecting and diagnosing disease. Unfortunately, the resolution of a standard ophthalmoscope is quite poor. Only the largest structures, such as major blood vessels and the optic nerve head, are visible - single cells are much to small to be resolved. This is because the surface of the cornea and lens are riddled with small imperfections.

Adaptive optics is a technology that allows us to fix those imperfections and see the very smallest structures - cone and rod photoreceptors.

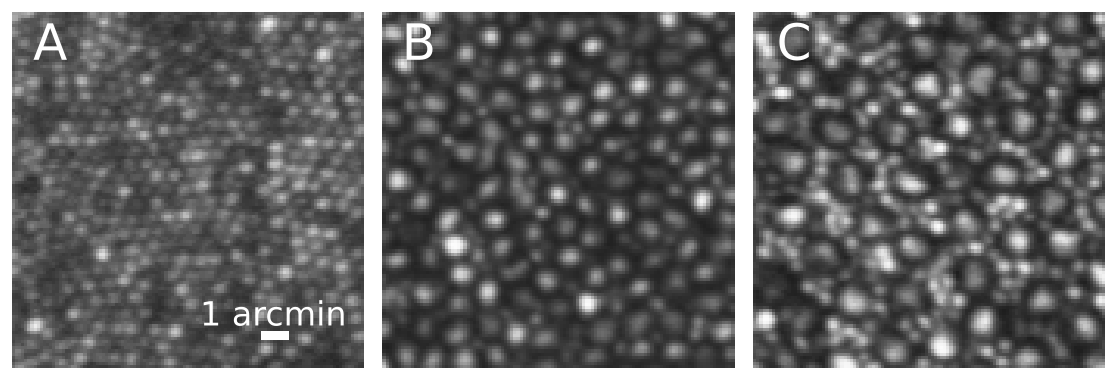

Above are a series of adaptive optics image taken of my right eye at three different retinal locations. The left image (A) was taken at the very center of my retina, the foveola. Cones here are very small (each blob is a single cone). This is the area used for reading fine print. The middle image (B) was 1.5 degrees away from the center of gaze. At this location cones become larger in size and rods (the smaller blobs) are found in about equal number to cones. The image to the right (C) was 5 degrees away from the foveola. Here rods become clearly visible and more numerous than cones. Scale bar = 1 arcmin or about 5 microns. For reference, the width of a human hair ranges from 30-100 microns.